ORANGE PEEL

ORANGE PEELGlass Fur

Alessandro Mercuri __ November 29, 2011

In Venus Heel, shoe designer Raphael Young explains: “When the sun goes down, I often start drawing. It's as if I needed everybody to be asleep and everything to be quiet before I can create in secret. And the next morning, I can show you my creations.” These words are somewhat reminiscent of the stories about master shoemakers, those craftsmen to be found in fairy tales.

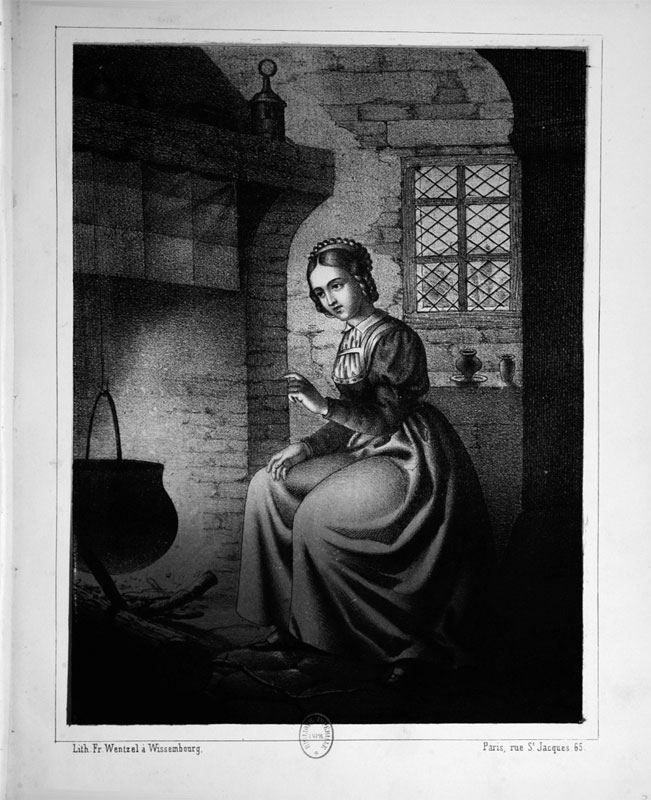

In 1697, under the reign of Louis the 14th, Charles Perrault published a collection of eight tales, Histories or Tales of Times Past, in which feet, shoes or boots played a prominent part in the narrative. “Little Thumb came up to the ogre, pulled off his boots gently and put them on his own feet. The boots were very long and large; but as they were Fairies, they had the gift of becoming big or little according to the legs of the person who was wearing them; so that they fit his feet and legs as well as if they had been made on purpose for him.” Perrault relates the adventures of a Little Thumb with seven-league boots, the tale of a Master Cat, or Puss in Boots and, the most famous of all, Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper. The reader will never know the real name of the small-footed heroin. For Cinderella is only a nickname. Humiliated by the two hateful daughters of her stepmother, Cinderella is denied an identity and thus deprived of a name. In the original French text, the most detestable of her step-sisters calls her “Cucendron” (often translated as “Cinderwench” in English), which should read “Cul-cendron”—meaning literally “ash-ass” or “with her ass in the cinders”. Her other step-sister calls her “Cendrillon”, the contraction of “cendre” (“cinder”) and “souillon” (“slovenly maid”). This portmanteau word reveals Perrault’s commitment to literature as such, i.e. as the creation of a language in itself.

The modernity of Perrault is proverbial. He initiated the quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns (1687), one of the first esthetical debates on the literary and artistic scene. One of his early works was indeed entitled The Walls of Troy or the Origin of Burlesque (1653). In one of the supplements to Papers on French Seventeenth Century Literature, Yvette Saupé explains how Perrault exceled at parodying, disparaging and distorting mythology. He displayed a satirical and polemical verve by juxtaposing styles—the noble versus the vulgar, diamonds versus manure.

But there is always somebody somewhere who is smarter than you. Long before the publication of Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Balzac was the first to revisit Perrault’s work, in the same way that Perrault had parodied classical writers. In About Catherine de' Medici (1842), one of the volumes of Philosophical Studies, Balzac reinterprets in his turn the glass slipper. Bettelheim insists on the erotic dimension of the foot as an organ and of the shoe as a sexual sheath. The symbolism of the foot and of the shoe, at the junction of Eros and Thanatos, is firmly rooted in popular culture, as shown by French phrases which are both sensual and morbid, mingling death and voluptuousness, such as: “prendre son pied” (literally “take one’s own foot”, that can be translated by “having an orgasm” or “sexual pleasure”) or “les pieds devant” (“feet first”). Same thing with the romantic expression “trouver chaussure à son pied”, literally “find the right shoe for one’s foot” (“find the perfect match”), although it is necessary to reverse it to fit the narrative logic at work in The little Glass Slipper; for in the wonderful land of fairies, it is usually “finding the right foot for one’s shoe” that matters. The tale bends the logic of language until distorting its syntax. As a matter of fact, the purpose of the Prince’s quest for love is not any longer the priceless shoe—which he already owns, fetishizes and cherishes—belonging to the beautiful stranger, but the precious foot which inhabits the shoe in all its nakedness. In order to marry his beloved, he will have to, against all grammatical expectations, “find the right foot for the shoe”. In the tale, the foot has its own logic, of which reason knows nothing. In the imaginary and fictitious world of Cinderella, where everything begins badly and ends well, the foot is the measure of all things. And it is the same in the real world. For it is reality as a whole which measures up to the “foot” as a unit of measurement, from the earth to the sky, from the dead to the living. The fatal phrase “to be six feet under” is evidence enough.

According to Bettelheim, it is probably not a coincidence if the author of the magical boots’ story has favored glass over leather, and this is how he describes the slipper: “a tiny receptacle into which some part of the body can slip and fit tightly can be seen as a symbol of the vagina. Something that is brittle and must not be stretched because it would break reminds us of the hymen.” But Balzac goes further and does not merely interpret. As a good author, a demiurge and a creator of worlds, the writer of the Human Comedy rewrites the history of literature. After all, why would this particular genre not be considered literature as well? According to Balzac, the title should be: Cinderella, or The Little Vair Slipper and not Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper (the words “vair”—the fur—and “verre”—“glass”—being homophones in French). Used to adorn garments, vair is the name given to the bluish-gray and white fur of a variety of squirrel. The glass slipper, being transparent, would then be similar to a jewel, whereas the vair slipper, being opaque, would be similar to a casket.

While Perrault plays with the nickname of his heroin—ashy-bottom, maid of soot—, Balzac acts as a master shoemaker of literature and as an inventor-tailor of true spelling: “In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, furriery was one of the most flourishing industries. Because of the difficulty of obtaining furs—which, being brought from the North, required long and perilous journeys—these products were excessively expensive. Then, as now, high prices led to consumption; for vanity knows no obstacles. In France, and in other kingdoms, not only did royal ordinances restrict the wearing of furs to the nobility, as proved by the importance of ermine in the old blazons, but also certain rare furs, such as vair, which was undoubtedly Siberian sable, could only be worn by kings, dukes and certain lords endowed with official powers. A distinction was made between the greater and lesser vair. Such has been the disuse of this word for a century that in a vast number of editions of Perrault's tales, Cinderella's famous slipper, which was no doubt of ‘vair’ (the fur), is said to have been made of ‘verre’ (glass).”

Is Cinderella’s foot molded in glass or sheathed in vair? The controversy remains, at least as a burlesque literary quarrel. Balzac’s interpretation, beyond the play-on-words, reminds us that ambivalence, polysemy and the derangement of the senses and of sense are at the heart of literature.

Alessandro Mercuri

(translated from the French by Blandine Longre and Paul Stubbs)

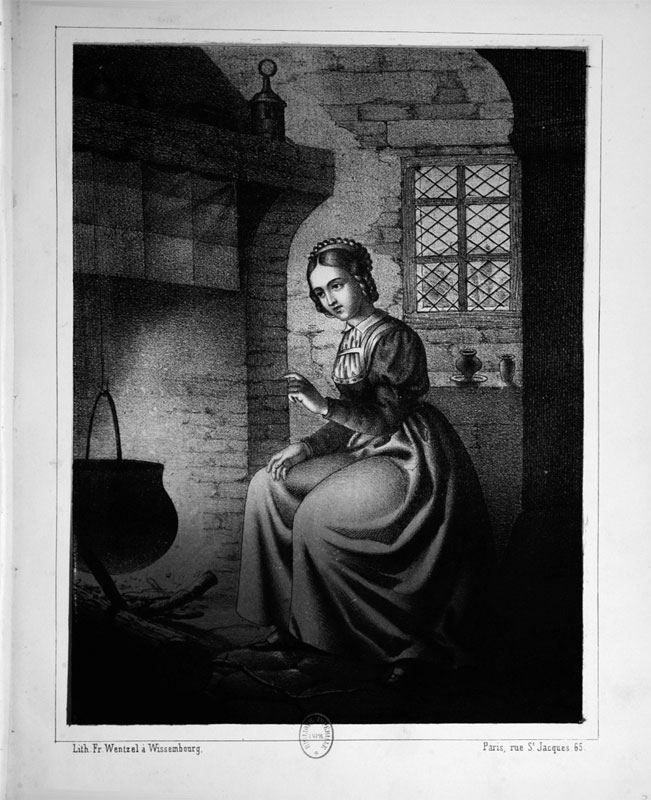

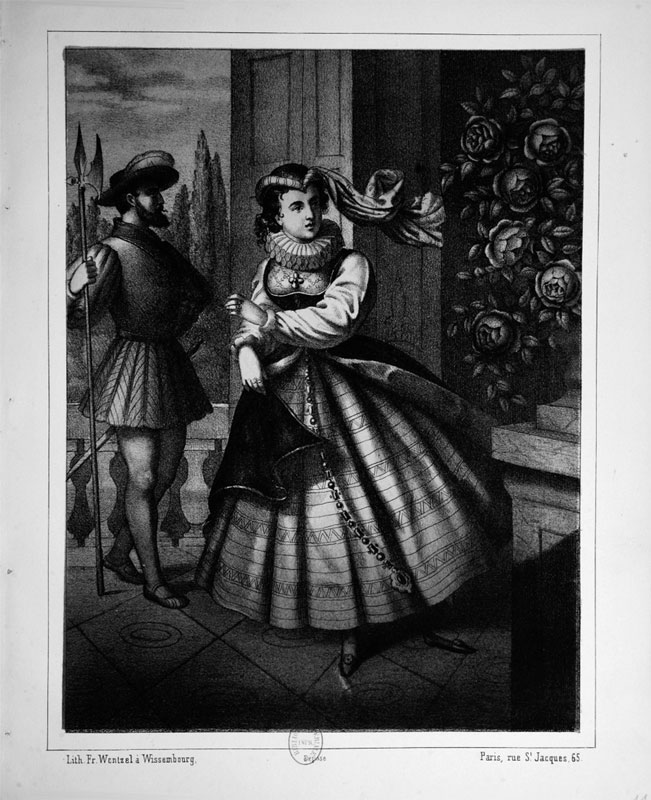

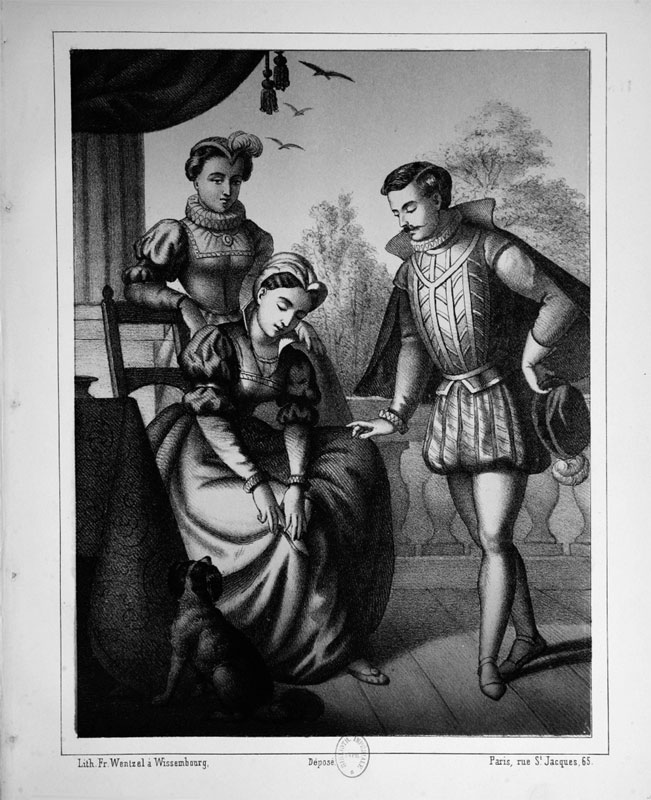

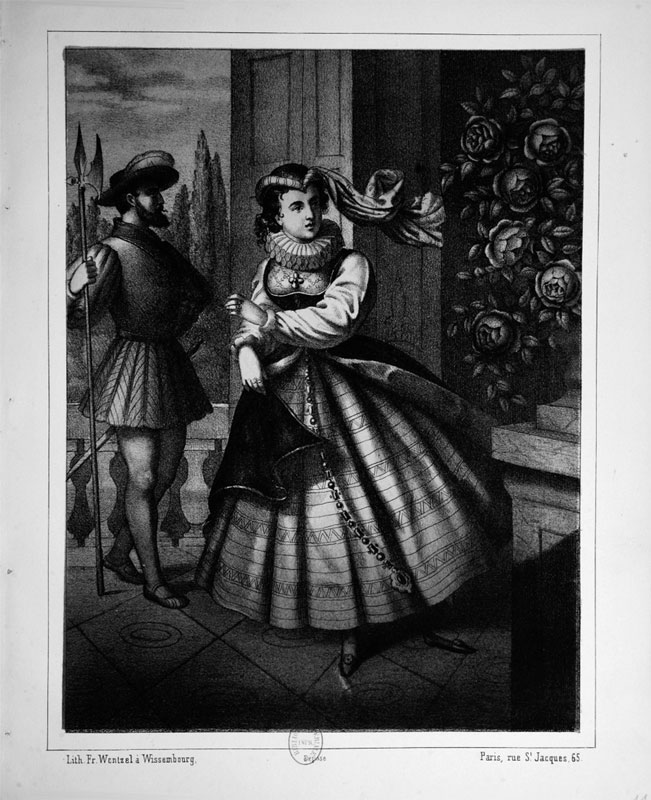

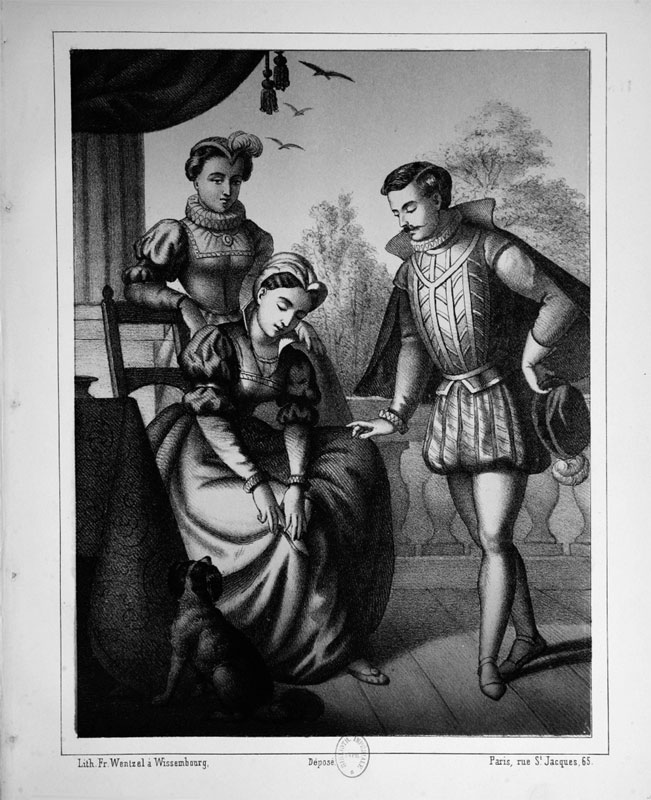

images : Cendrillon

publisher : Fr. Wentzel

lithography : Ch. Wentzel (1868)

source : Gallica - Bibliothèque nationale de France

In 1697, under the reign of Louis the 14th, Charles Perrault published a collection of eight tales, Histories or Tales of Times Past, in which feet, shoes or boots played a prominent part in the narrative. “Little Thumb came up to the ogre, pulled off his boots gently and put them on his own feet. The boots were very long and large; but as they were Fairies, they had the gift of becoming big or little according to the legs of the person who was wearing them; so that they fit his feet and legs as well as if they had been made on purpose for him.” Perrault relates the adventures of a Little Thumb with seven-league boots, the tale of a Master Cat, or Puss in Boots and, the most famous of all, Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper. The reader will never know the real name of the small-footed heroin. For Cinderella is only a nickname. Humiliated by the two hateful daughters of her stepmother, Cinderella is denied an identity and thus deprived of a name. In the original French text, the most detestable of her step-sisters calls her “Cucendron” (often translated as “Cinderwench” in English), which should read “Cul-cendron”—meaning literally “ash-ass” or “with her ass in the cinders”. Her other step-sister calls her “Cendrillon”, the contraction of “cendre” (“cinder”) and “souillon” (“slovenly maid”). This portmanteau word reveals Perrault’s commitment to literature as such, i.e. as the creation of a language in itself.

The modernity of Perrault is proverbial. He initiated the quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns (1687), one of the first esthetical debates on the literary and artistic scene. One of his early works was indeed entitled The Walls of Troy or the Origin of Burlesque (1653). In one of the supplements to Papers on French Seventeenth Century Literature, Yvette Saupé explains how Perrault exceled at parodying, disparaging and distorting mythology. He displayed a satirical and polemical verve by juxtaposing styles—the noble versus the vulgar, diamonds versus manure.

But there is always somebody somewhere who is smarter than you. Long before the publication of Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Balzac was the first to revisit Perrault’s work, in the same way that Perrault had parodied classical writers. In About Catherine de' Medici (1842), one of the volumes of Philosophical Studies, Balzac reinterprets in his turn the glass slipper. Bettelheim insists on the erotic dimension of the foot as an organ and of the shoe as a sexual sheath. The symbolism of the foot and of the shoe, at the junction of Eros and Thanatos, is firmly rooted in popular culture, as shown by French phrases which are both sensual and morbid, mingling death and voluptuousness, such as: “prendre son pied” (literally “take one’s own foot”, that can be translated by “having an orgasm” or “sexual pleasure”) or “les pieds devant” (“feet first”). Same thing with the romantic expression “trouver chaussure à son pied”, literally “find the right shoe for one’s foot” (“find the perfect match”), although it is necessary to reverse it to fit the narrative logic at work in The little Glass Slipper; for in the wonderful land of fairies, it is usually “finding the right foot for one’s shoe” that matters. The tale bends the logic of language until distorting its syntax. As a matter of fact, the purpose of the Prince’s quest for love is not any longer the priceless shoe—which he already owns, fetishizes and cherishes—belonging to the beautiful stranger, but the precious foot which inhabits the shoe in all its nakedness. In order to marry his beloved, he will have to, against all grammatical expectations, “find the right foot for the shoe”. In the tale, the foot has its own logic, of which reason knows nothing. In the imaginary and fictitious world of Cinderella, where everything begins badly and ends well, the foot is the measure of all things. And it is the same in the real world. For it is reality as a whole which measures up to the “foot” as a unit of measurement, from the earth to the sky, from the dead to the living. The fatal phrase “to be six feet under” is evidence enough.

According to Bettelheim, it is probably not a coincidence if the author of the magical boots’ story has favored glass over leather, and this is how he describes the slipper: “a tiny receptacle into which some part of the body can slip and fit tightly can be seen as a symbol of the vagina. Something that is brittle and must not be stretched because it would break reminds us of the hymen.” But Balzac goes further and does not merely interpret. As a good author, a demiurge and a creator of worlds, the writer of the Human Comedy rewrites the history of literature. After all, why would this particular genre not be considered literature as well? According to Balzac, the title should be: Cinderella, or The Little Vair Slipper and not Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper (the words “vair”—the fur—and “verre”—“glass”—being homophones in French). Used to adorn garments, vair is the name given to the bluish-gray and white fur of a variety of squirrel. The glass slipper, being transparent, would then be similar to a jewel, whereas the vair slipper, being opaque, would be similar to a casket.

While Perrault plays with the nickname of his heroin—ashy-bottom, maid of soot—, Balzac acts as a master shoemaker of literature and as an inventor-tailor of true spelling: “In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, furriery was one of the most flourishing industries. Because of the difficulty of obtaining furs—which, being brought from the North, required long and perilous journeys—these products were excessively expensive. Then, as now, high prices led to consumption; for vanity knows no obstacles. In France, and in other kingdoms, not only did royal ordinances restrict the wearing of furs to the nobility, as proved by the importance of ermine in the old blazons, but also certain rare furs, such as vair, which was undoubtedly Siberian sable, could only be worn by kings, dukes and certain lords endowed with official powers. A distinction was made between the greater and lesser vair. Such has been the disuse of this word for a century that in a vast number of editions of Perrault's tales, Cinderella's famous slipper, which was no doubt of ‘vair’ (the fur), is said to have been made of ‘verre’ (glass).”

Is Cinderella’s foot molded in glass or sheathed in vair? The controversy remains, at least as a burlesque literary quarrel. Balzac’s interpretation, beyond the play-on-words, reminds us that ambivalence, polysemy and the derangement of the senses and of sense are at the heart of literature.

Alessandro Mercuri

(translated from the French by Blandine Longre and Paul Stubbs)

images : Cendrillon

publisher : Fr. Wentzel

lithography : Ch. Wentzel (1868)

source : Gallica - Bibliothèque nationale de France

TAGS : Glass Fur, Venus Heel, shoe designer, Raphael Young, fairy tales, Louis the 14th, Charles Perrault, Histories or Tales of Times Past, Cinderella, The Little Glass Slipper, Cinderwench, portmanteau, Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, The Walls of Troy or the Origin of Burlesque, Yvette Saupé, Papers on French Seventeenth Century Literature, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, Bruno Bettelheim, Honoré de Balzac, The Little Vair Slipper, Ch. Wentzel

NEXT POST >>